Pseudoproxy modelling of uncertainties in palaeoecological data.

Quinn Asena, George Perry, Janet Wilmshurst

University of Auckland, UW-Madison

12/8/22

The problem

Proxy data are the product of multiple sources of uncertainty

Environmental processes

- bioturbation, taphonomy, variable sedimentation rates…

Field and laboratory methods

- core collection methods, sub-sampling strategy, pollen counting…

Data processing methods

- age-depth modelling, interpolation…

The question: is the past recoverable from the data?

Why it matters

Palaeoecology moving from descriptive to quantitative

Palaeoecology to inform the future requires robust statistical approaches

Advances in lab methods, data availability, and statistics are making more inferences possible

What we can do about it

- One method to assess uncertainties is in simulation

Approach and take-home

Simulate core samples containing proxies that mimic the statistical properties of empirical data

Simulate uncertainties: process and observer error that affect the data

Assess how statistical inferences are affected by those uncertainties

Key concepts

Virtual ecology (Zurell et al. 2010)

Proxy system modelling (Evans et al. 2013)

Pseudoproxy experiments (Mann and Rutherford 2002)

Other key refs:

Virtual ecology

Virtual ecology is a framework for assessing sampling and analytical methods in simulation consisting of:

an ecological model that generates synthetic data

1a. a degradation model

a simulated observational process (a sampling model) that samples the synthetic data

an analytical process or statistical model applied to both sets of data

an assessment of the results

Virtual ecology and empirical ecology

Perfect knowledege, imperfect world

known drivers and responses

known environmental and observational processes

Advantage of benchmark/control data

Advantage of replication

Able to systematically introduce uncertainty

Perfect world, imperfect knowledge

Sampled data with no benchmark/control

Advantage of being reality

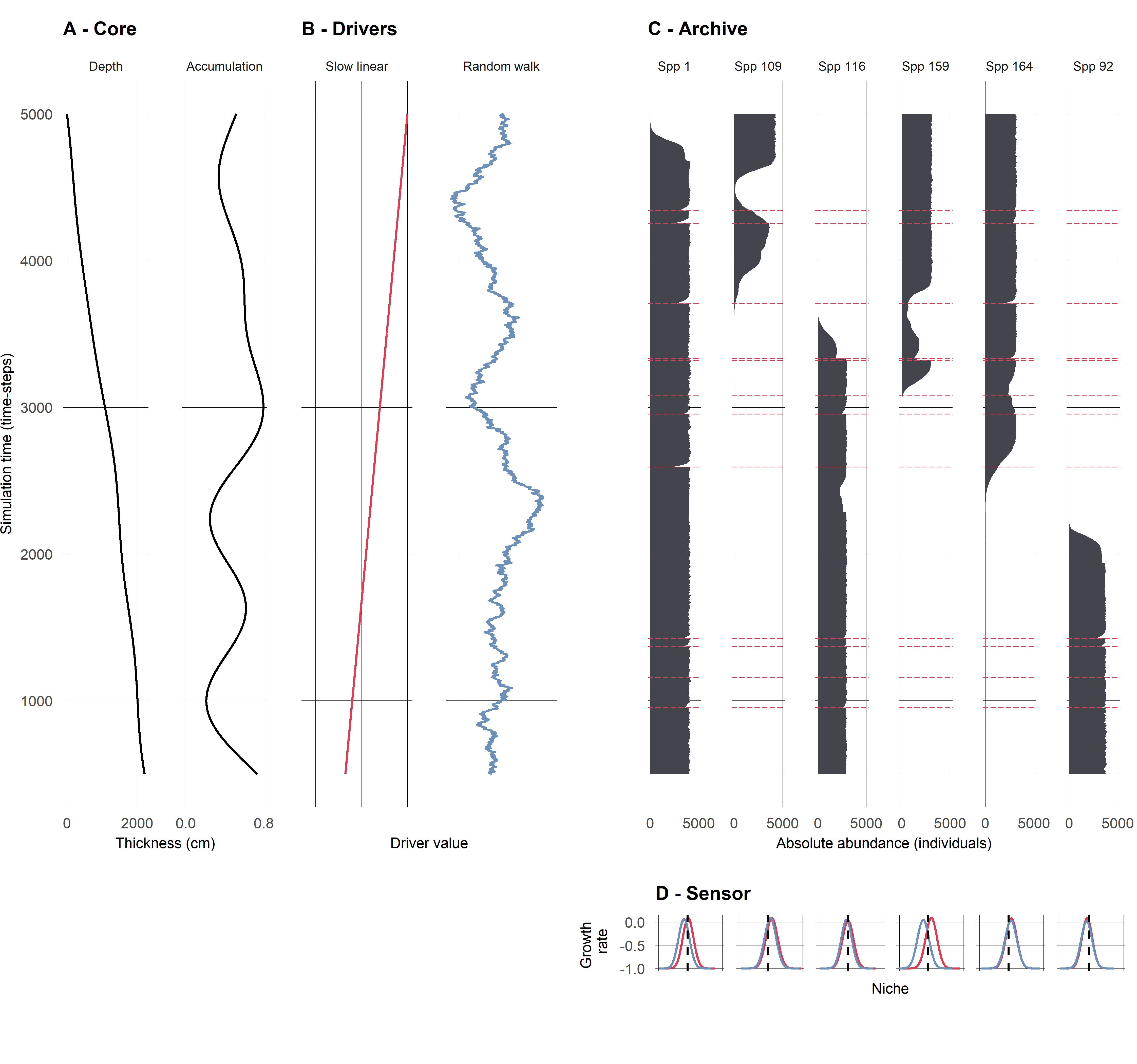

Proxy system modelling

Describes the process by which environmental change is recorded as an observable signal in an archive:

environmental drivers (e.g., climatic variability)

a sensor (a physical, biological or chemical component of the system that responds to the environmental drivers)

an archive (the medium in which the response of the sensor is recorded such as a lake sediment)

observations drawn from the archive

Proxy Ststem Modelling framework, from Evans et al. (2013)

Pseudoproxy experiments

Borrowing the term “pseudoproxies” from climatology:

pseudoproxies are simulated data or modified observational data

mimic the statistical properties of empirical data

pseudoproxy experiments are similar to virtual ecology

Building the model

Simulating pseudoproxies

We set out to:

Represent multiple interacting drivers

Include underlying ecological dynamics that can undergo community turnover

Generate a multi-species pseudoproxy

Recreate core formation processes of accumulation rates and time-span

Virtually recreate the observational processes

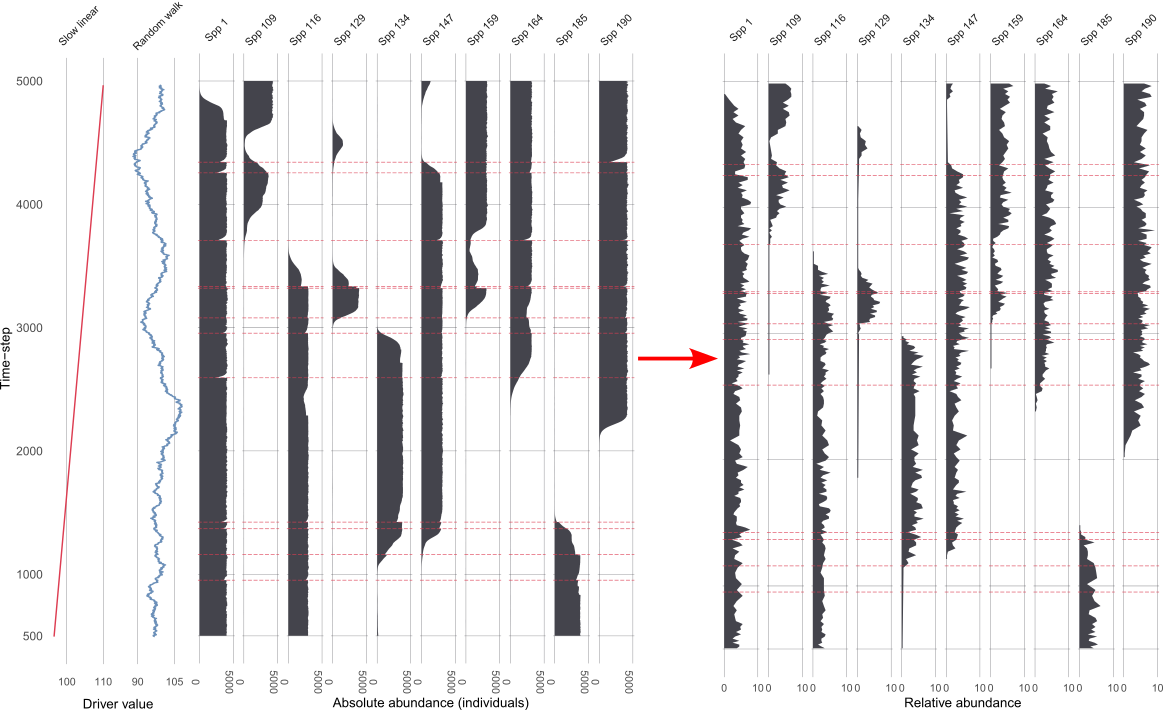

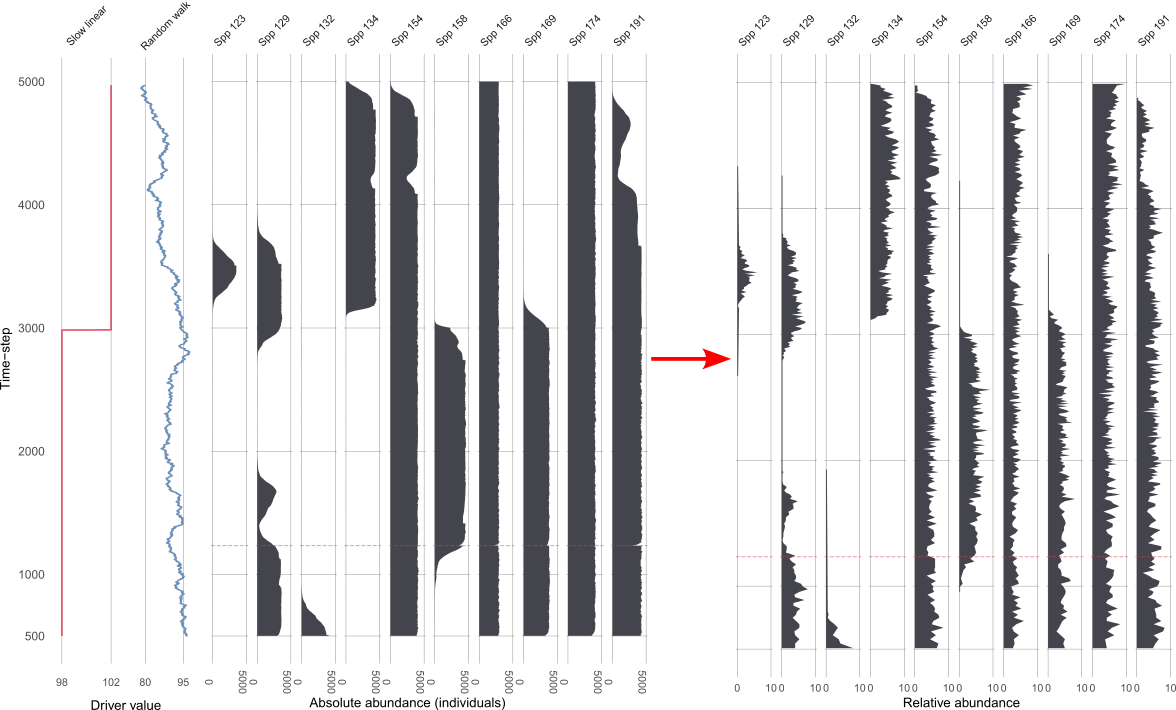

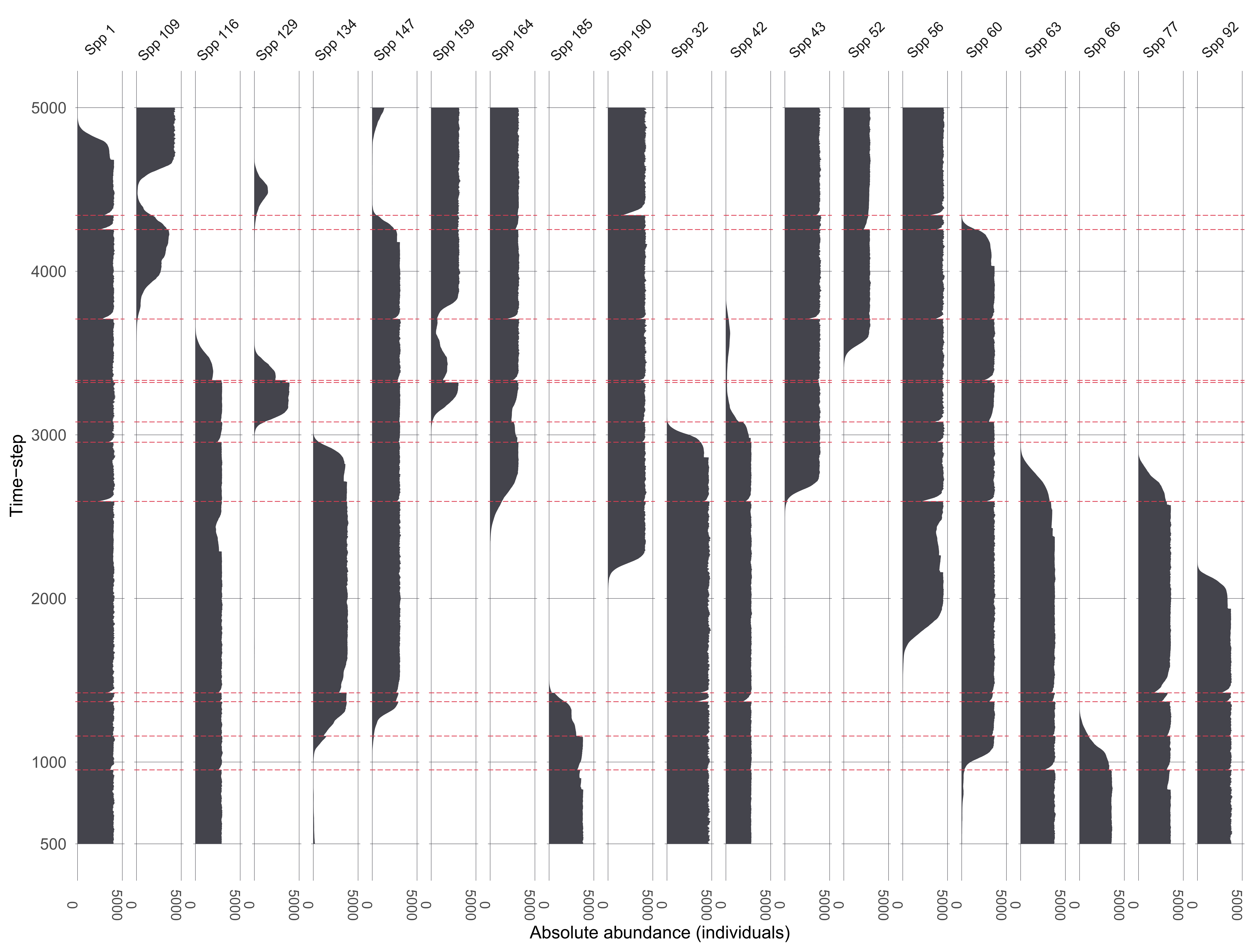

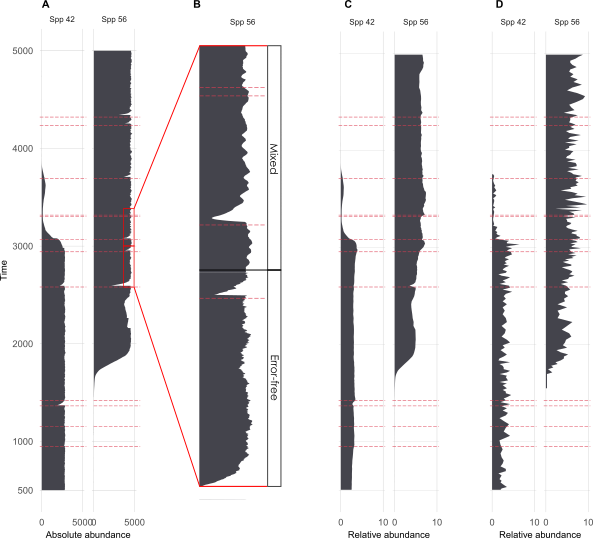

Simulating pseudoproxies

Ruining pseudoproxies

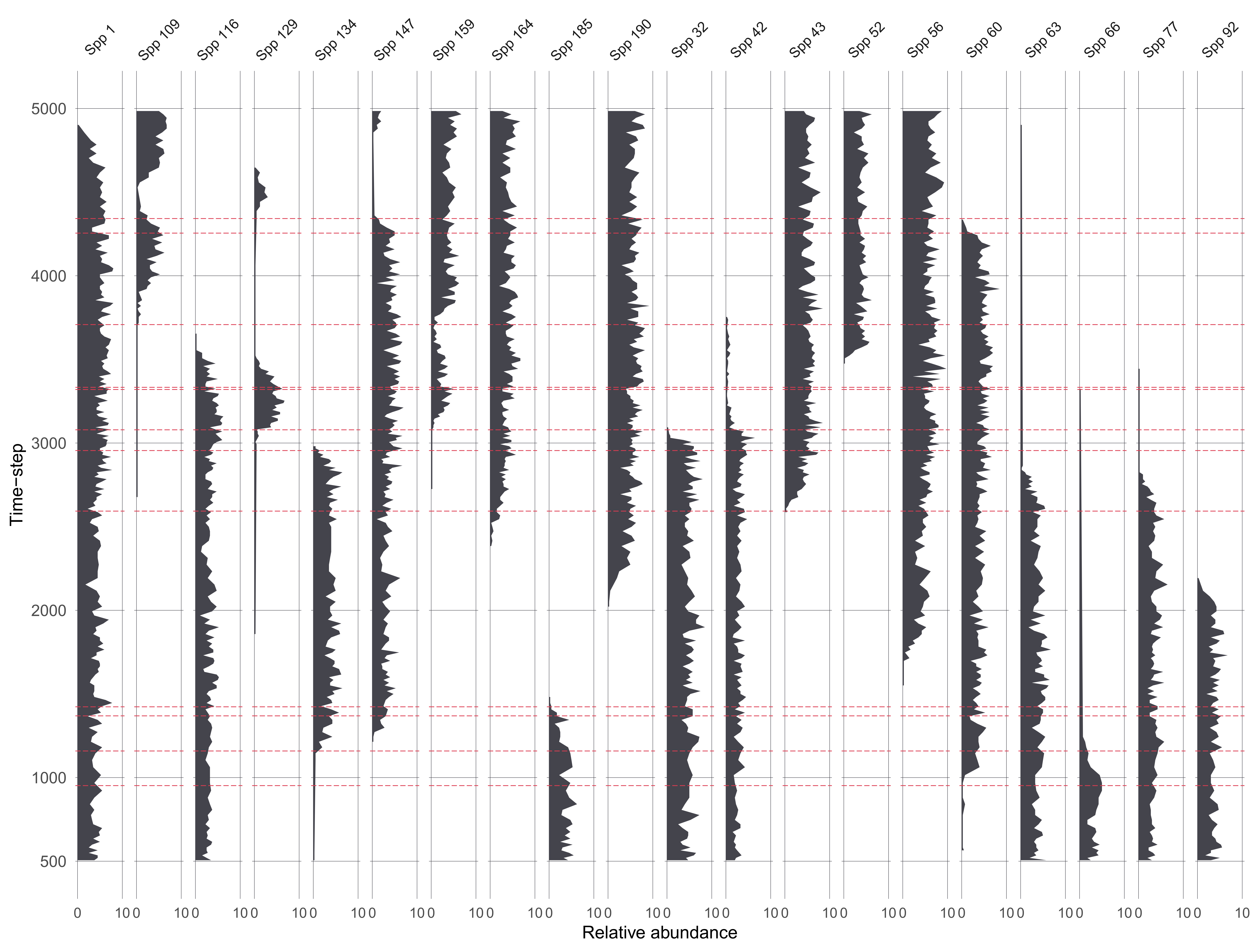

A. Example species from single replicate

B. Mixing

C. Mixing + sub-sampling

D. Mixing + sub-sampling + proxy counting

Ruined pseudoproxies

Applying the model

Analyses

Ok, now we have generated the data, let’s analyse it. Two analyses:

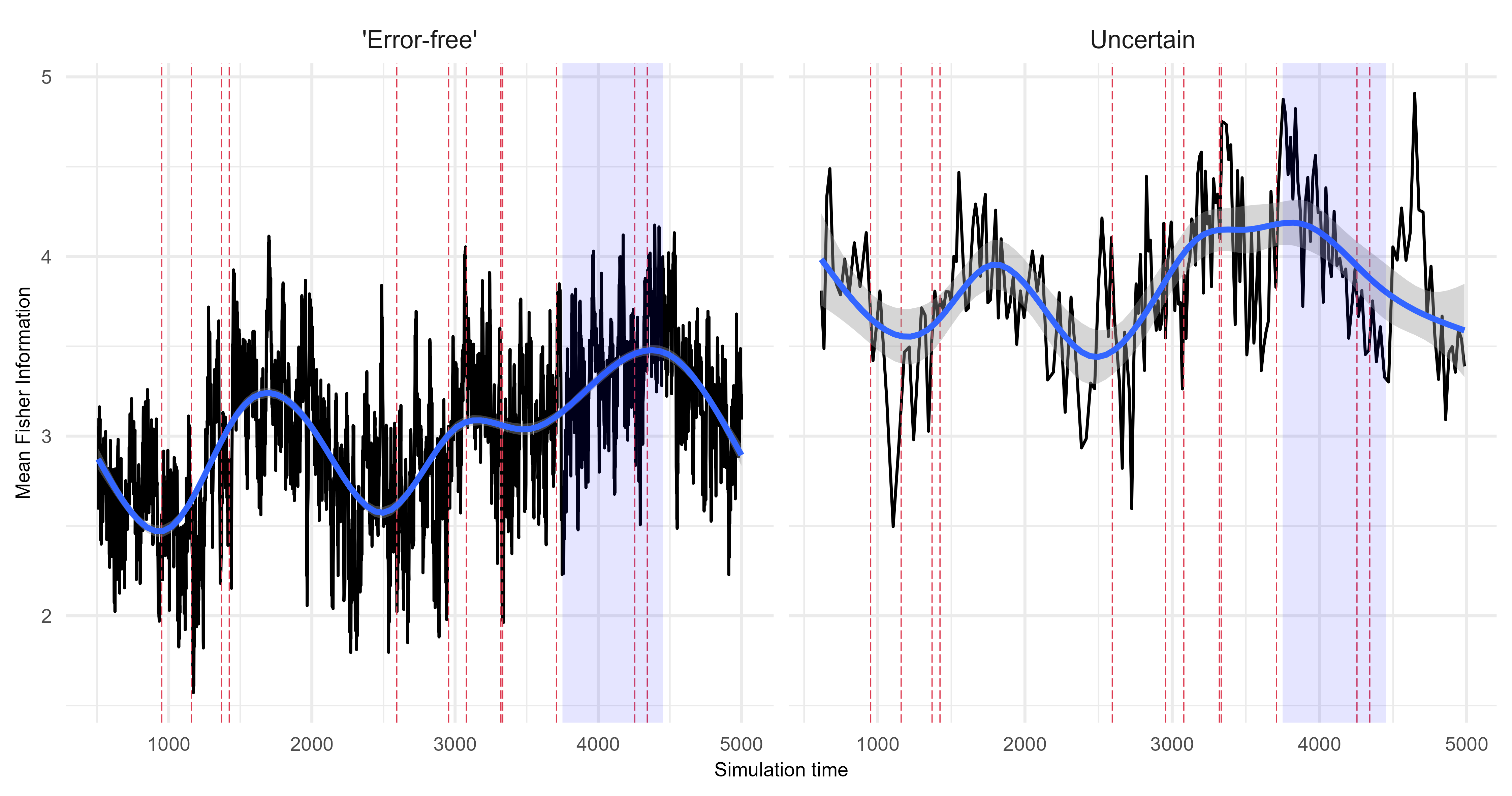

Fisher Information

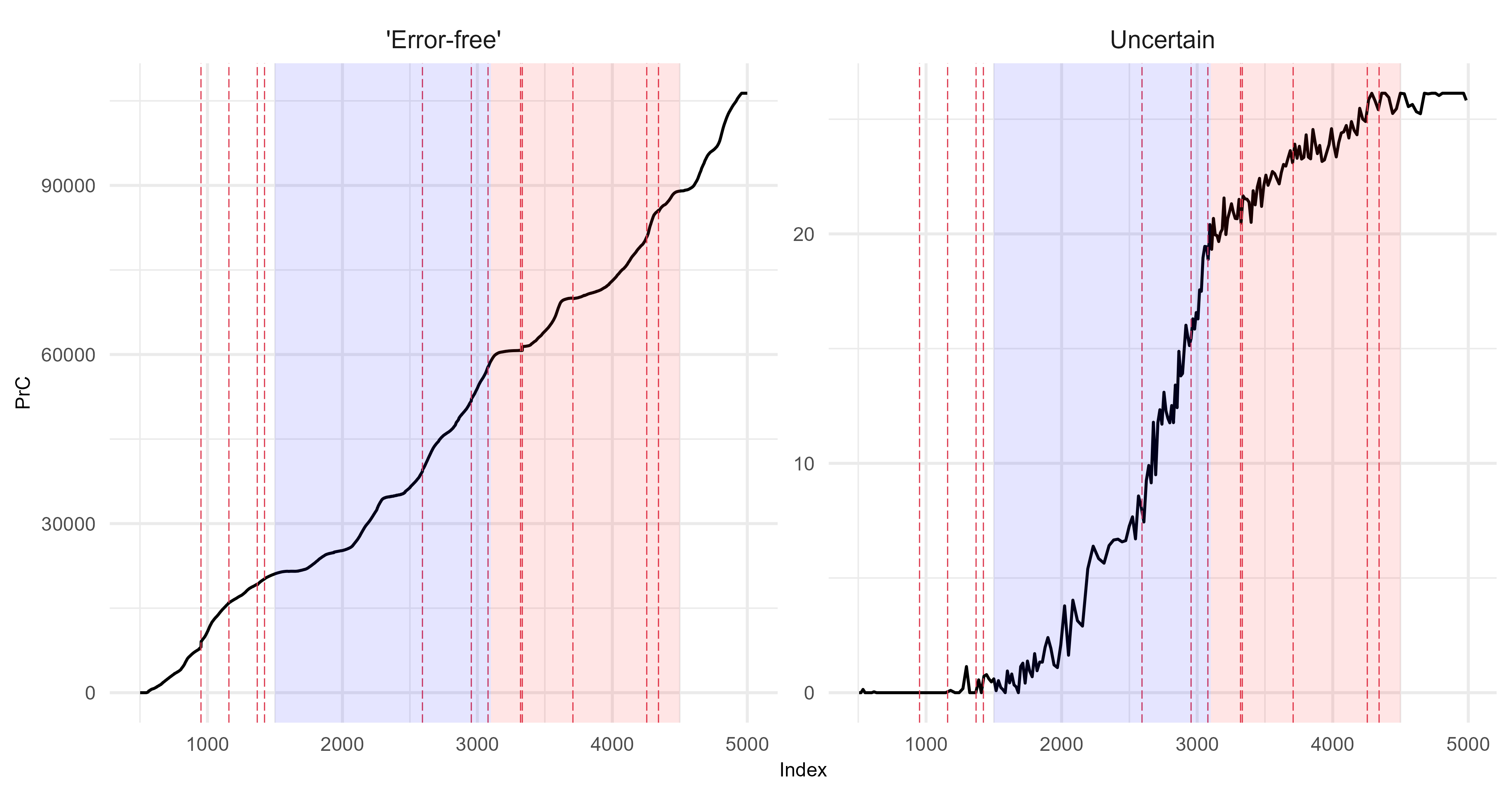

Principal curves

Demonstrating two scenarios with different driving environments.

Scenario 1

Scenario 2

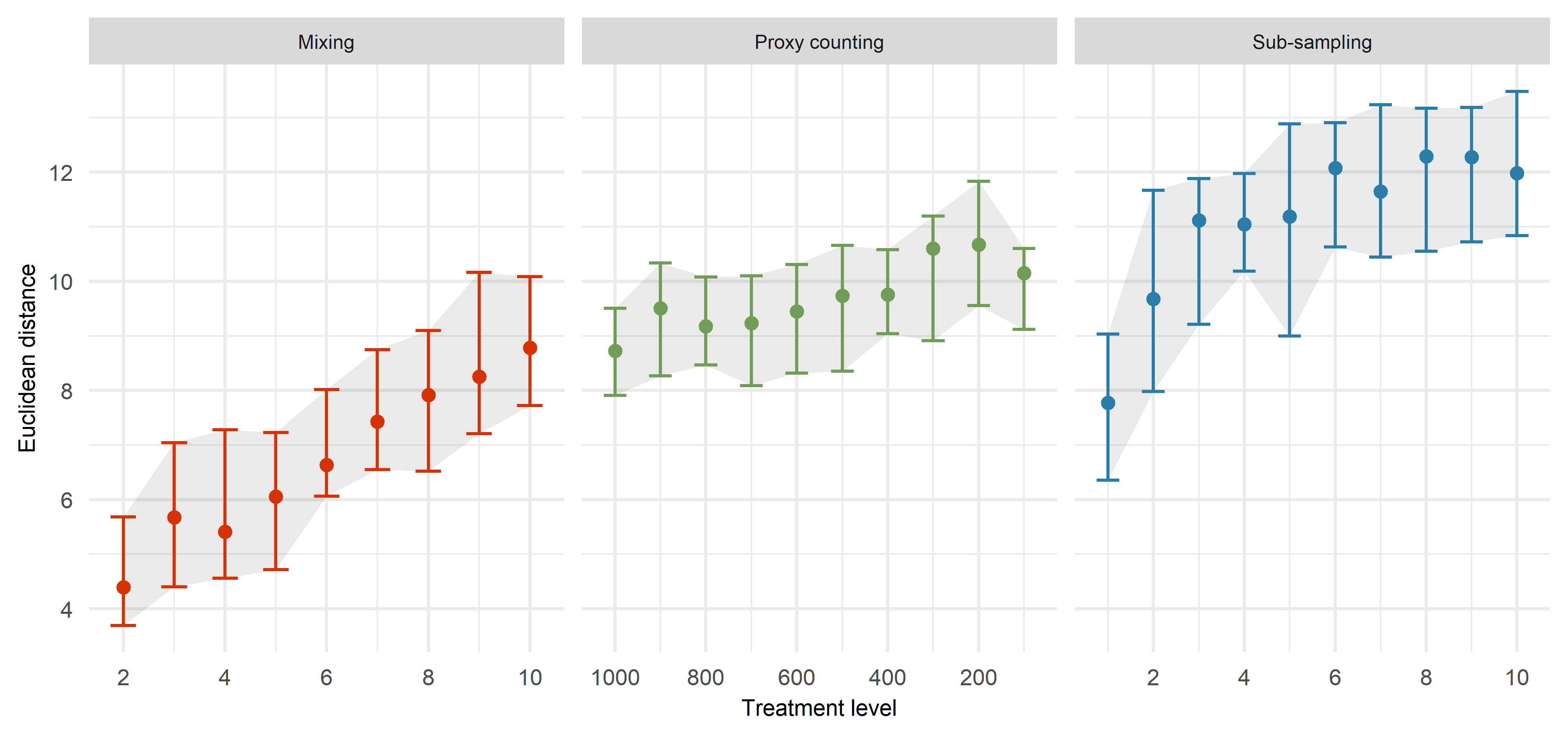

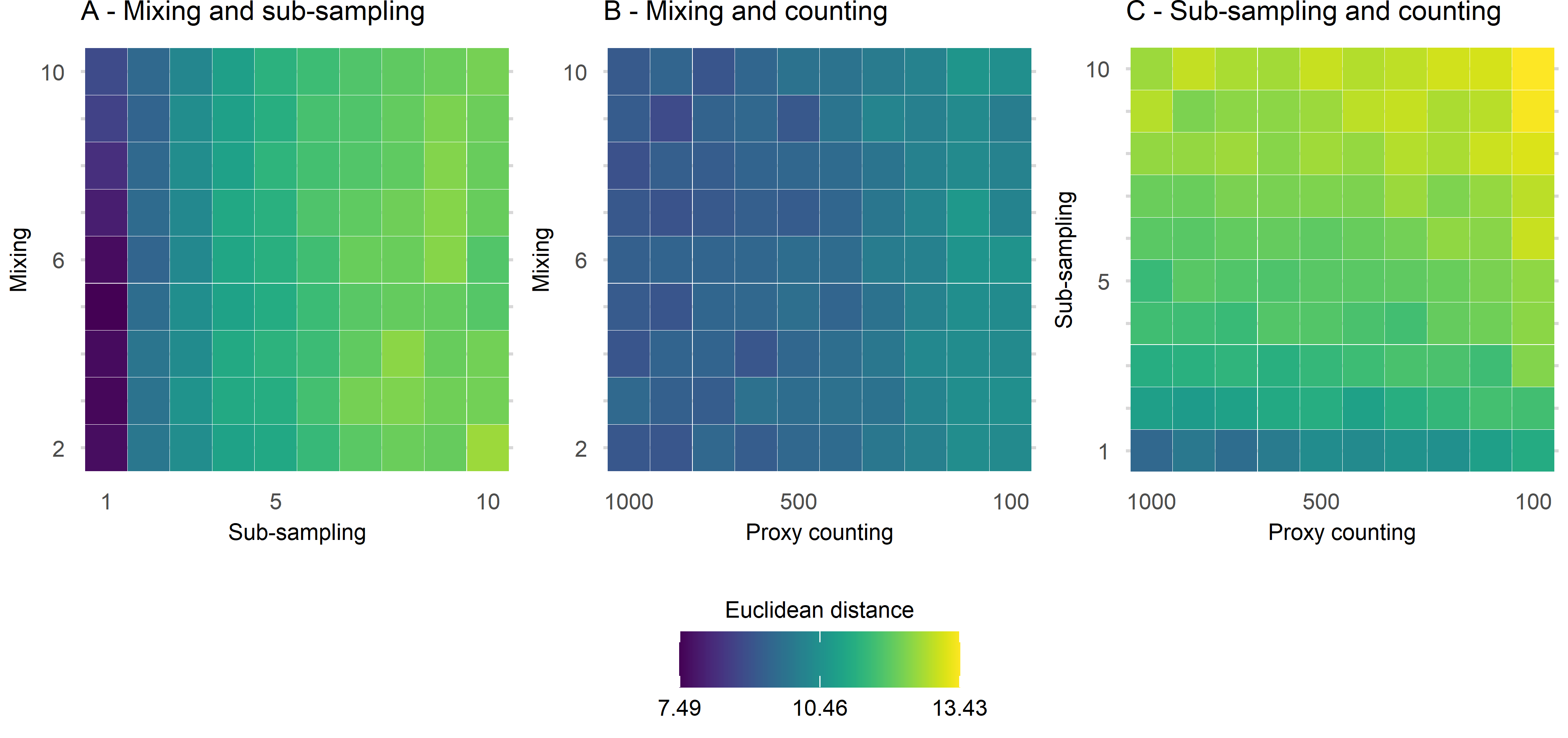

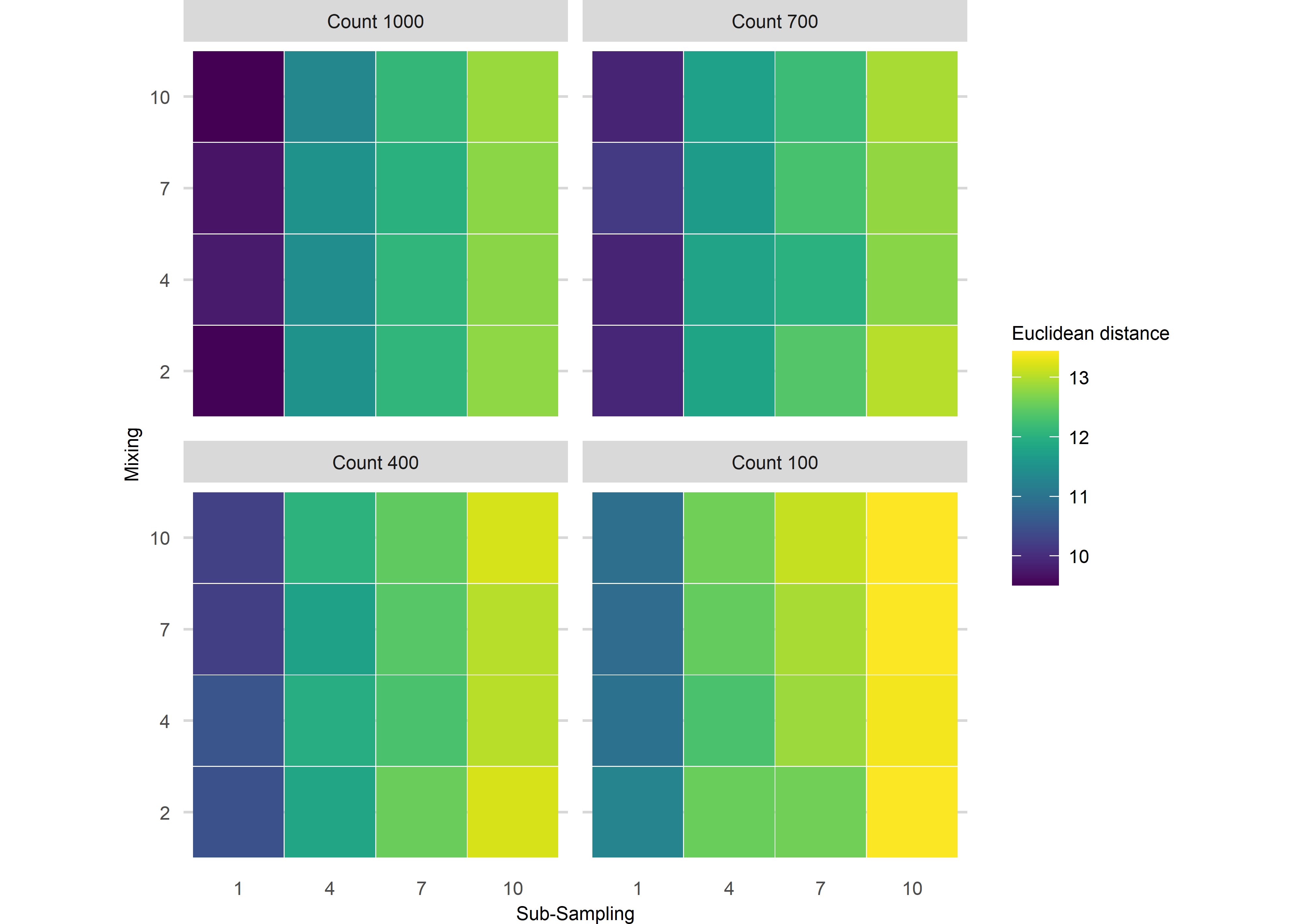

Assessing uncertainties across replicates

Each replicate results in 1210 datasets from the ‘error-free’ to the most uncertain, per scenario 😱.

Across replicates for each of the 1210 datasets:

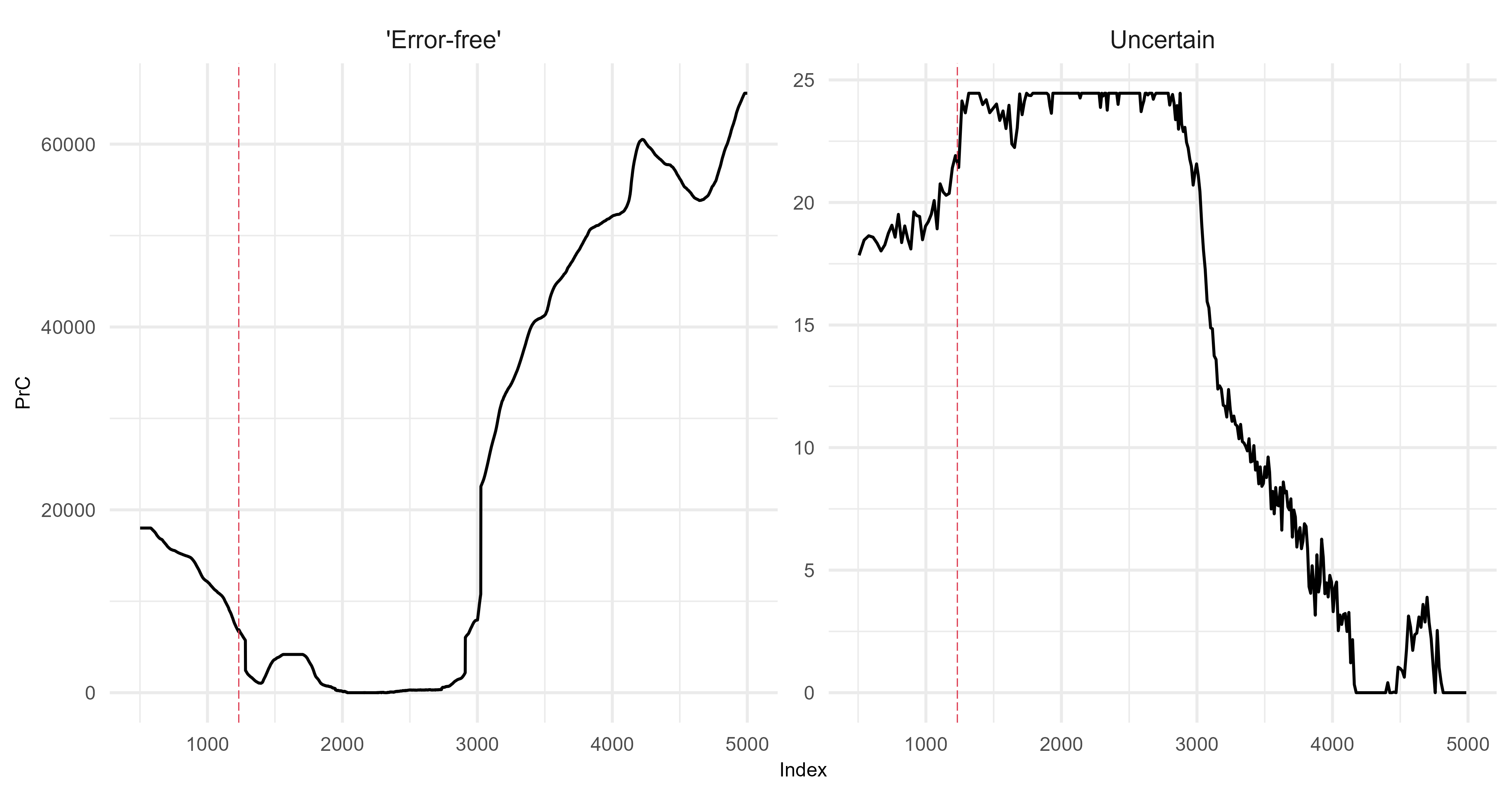

extract features from the FI and PrC

- feature analysis reduces the FI and PrC to one dimension

calculate the distance between each dataset from the ‘error-free’ to the most uncertain

make cool visulisations!

Assessing uncertainties across replicates

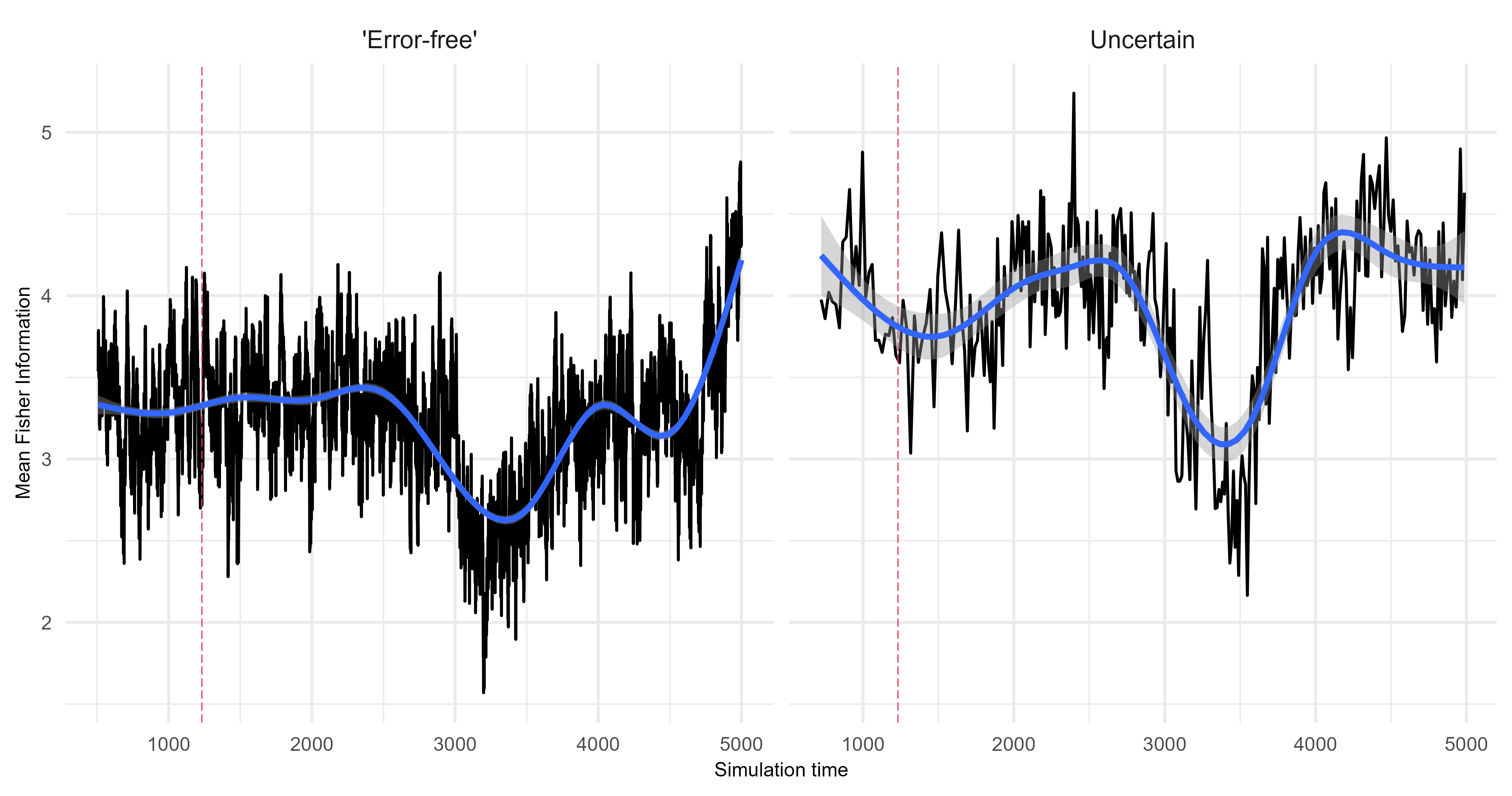

Quantify the difference between the ‘error-free’ archive and each level of uncertainty. The following is an example from scenario 1 using Fisher Information.

Assessing uncertainties across replicates

Application to empirical

Simulation methods can be integrated with empirical studies to:

a priori help shape field sampling methods: e.g., number of core samples (across a region or local replication) required for a given research question.

understand the sub-sampling and count resolution required to increase the likelihood of detecting a hypothesised signal in the data.

accompany empirical study to test hypotheses about the underlying dynamics that may cause an observed pattern in the data.

assess whether inferences made from the data are robust to uncertainty.

What I haven’t covered

“All models are wrong, some are useful” Box (1979)

Assessing error rates

Chronological uncertainty

Extend underlying dynamics to ask specific questions (e.g., resilience)

Acknowledgements

George Perry (University of Auckland) and Janet Wilmshurs (University of Auckland, and Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research)

Jack Williams and Tony Ives (University of Wisconsin Madison)

Biological heritage Science Challenge (NZ) and the National Science Foundation (USA)